NASA’s lunar reactor push: Science, security, and the space race

Experts say NASA’s plan to set up a nuclear reactor on the moon could transform lunar exploration and marks a long-awaited step toward making human presence in space sustainable

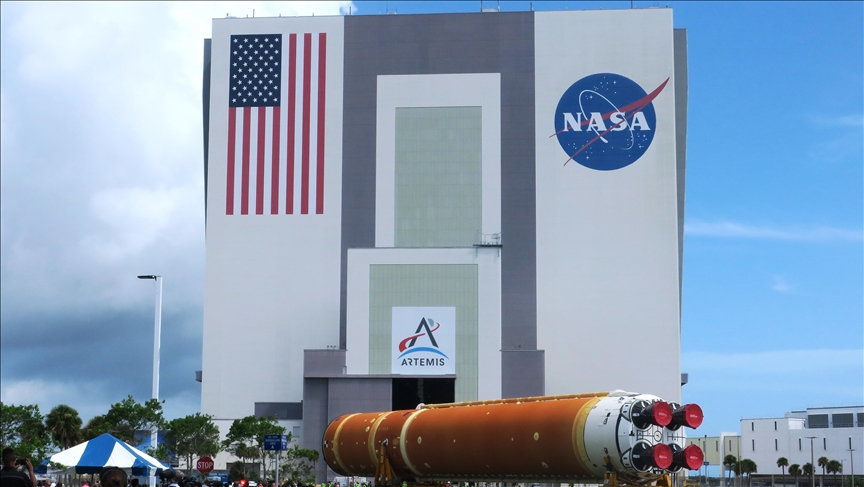

Workers transport the 212-foot-tall SLS core stage for the Artemis II moon rocket into the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on July 24, 2024 in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Workers transport the 212-foot-tall SLS core stage for the Artemis II moon rocket into the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on July 24, 2024 in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

- The initiative comes amid growing competition from China and Russia, who are also racing to establish nuclear power infrastructure on the moon

- The NASA announcement … is a welcome step. For decades, we have lacked exactly this kind of clear, deadline-driven target. It is especially encouraging that the directive focuses on power,’ former NASA official Bhavya Lal tells Anadolu

ISTANBUL

As competition in space exploration intensifies, the US has set its sights on a major milestone: installing a nuclear reactor on the moon by 2030.

NASA officials say the project could transform lunar exploration by providing reliable energy for permanent settlements, scientific research, and future missions to Mars. For scientists, it marks a long-awaited step toward making human presence in space sustainable.

“The NASA announcement of a lunar reactor by 2030 is a welcome step. For decades, we have lacked exactly this kind of clear, deadline-driven target. It is especially encouraging that the directive focuses on power, because without abundant, sustained power, everything else in space is temporary,” Bhavya Lal, NASA’s former associate administrator for technology, policy and strategy, told Anadolu.

The initiative comes amid growing competition from China and Russia, who are also racing to establish nuclear power infrastructure on the moon. With geopolitical rivalries now reaching beyond Earth, experts describe the plan as both ambitious and fraught with technical, safety, and geopolitical challenges.

Why nuclear power matters on the moon

Solar energy has long powered satellites, space stations, and landers. But on the moon, with its 28-day rotation cycle, sunlight disappears for two Earth weeks at a time. That makes solar panels alone an unreliable energy source.

A nuclear reactor can provide a continuous source of energy anywhere on the moon, explained Simeon Barber, a research scientist at The Open University.

“Solar panels only generate power when the sun is shining. On the moon, the night-time lasts for around 14 Earth days, so another energy source is needed to keep equipment – and astronauts – warm and safe through the lunar night.”

British volcanologist Lionel Wilson, stressing that the reactor is a “very good idea,” simplified it further: “You get 14 days of free electricity if you have lots of solar panels. But then you get 14 days of no sunlight … and if anything goes wrong with storage systems, you get very cold, very fast. Temperatures can fall to about minus 173C (minus 279F).”

Where could the nuclear reactor be built?

Most experts believe the first lunar reactor will be built near the moon’s south pole, a region of growing strategic importance.

“This is a strategically important region because it is thought to harbor large quantities of water ice. This could be extracted to provide water for drinking and sanitation in a lunar base,” said Barber.

“Or it could be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen to create a ‘fuel station’ on the moon for rockets heading to Mars.”

Wilson, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Lancaster University, noted that NASA’s current plan to place a base near the South Pole helps mitigate the problem of prolonged darkness.

“Close to the poles, there are places where the sun should be just above the horizon all the time, so those places should get permanent sunlight,” he explained.

But with rough terrain and crater shadows still blocking light at intervals, “batteries and a nuclear backup system are still needed,” he added.

A new space race

The US is not alone in this pursuit. In May, China and Russia jointly announced plans to build an automated nuclear power station on the moon by 2035 as part of their International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project.

US officials acknowledge the rivalry, with Politico reporting that NASA's acting head Sean Duffy referred to similar plans by China and Russia and warned that the two countries “could potentially declare a keep-out zone” on the moon.

For Barber, the stakes are more than symbolic.

“There is the symbolism and technological advantage of establishing the first energy infrastructure on the moon,” he said. “But also, current space regulations give some protection to equipment that is installed there – a ‘safety zone’ can be declared around equipment which in effect establishes control over regions of the moon.”

Is it safe to launch nuclear material into space?

Launching nuclear material into orbit inevitably raises fears. Barber acknowledged the risks but argued they are manageable.

“There is always a risk of failure in the rocket launch, meaning potential release of radioactive material into the Earth’s atmosphere. But in reality, the quantities of fuel involved are relatively modest, so the risks can – and will – be managed.”

Wilson said the likely fuel would be plutonium, not uranium, with detailed protocols already in place from previous deep-space missions. “Reactor designs go to great lengths to minimize risk,” he said.

“Small nuclear power sources are already used on spacecraft traveling to outer parts of the solar system, where sunlight is too weak to power solar panels. There should not be too many engineering problems in making bigger systems.”

Can the US deliver, and what comes next?

Skeptics point out that the US has a history of failed space nuclear initiatives. The last operational fission reactor in space was SNAP-10A satellite reactor in 1965, while programs such as SP-100 and Prometheus consumed billions but were eventually canceled.

Barber called the current timeline “very ambitious,” especially given NASA’s budget pressures: “At a time when the budget for space and Earth science is under huge pressure at NASA, this will only increase the squeeze.”

Lal, who recently co-authored a report titled Weighing the Future: Strategic Options for US Space Nuclear Leadership, said success requires government commitment comparable to the Manhattan Project, which produced America’s first atomic bombs.

“The Manhattan Project’s first test was not built on one laboratory or one company. It succeeded because the government created the conditions: adequate funding, parallel bets across technologies, empowered leadership, and a sense of strategic urgency. Those same conditions … must underpin space nuclear (efforts) today.”

The report estimates the program will need at least $2 billion to $3 billion in the first five years, along with investment in fuel infrastructure, safety reviews, regulatory reforms, and White House-level leadership.

Lal reaffirmed that NASA’s announcement is the right target, but emphasized the challenges ahead: “Now comes the hard part: building the system around it – so that this time, unlike the last 60 years, we actually fly.”

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.