South Korean adoptees struggle with US citizenship policies

Adoptees caught between 2 countries' past policies, leaving some stateless

ISTANBUL

The journey of foster children does not end when they are united with their families, sometimes after months or years of searching.

Many struggle to integrate into their new families and society, often without any support, while dealing with complex emotions.

Additionally, adoptees who were brought to the US years ago but never completed the citizenship process face the threat of deportation. If forced to leave the country they grew up in, they find themselves in an unfamiliar world -- one where they neither speak the language nor understand the culture of their birth country.

In the third and final part of the Anadolu news file titled “South Korea’s Adopted Children,” the perspectives of South Korean adoptees in the US are highlighted. They share their views on international adoption policies and the statements made by South Korea and the US.

Citizenship issues and deportation risks for adoptees

Many international adoptees in the US face the risk of deportation if they have not completed the citizenship process. Daniel Yoon, a lawyer at the non-governmental organization, Adoptees For Justice, which provides legal support for intercountry adoptees, explained that some individuals adopted into the US never had their citizenship finalized.

As a result, some adoptees have been subject to immigration laws and forcibly deported to South Korea, a country where they neither speak the language nor have access to essential services like health care. This has created significant challenges for deported adoptees, Yoon noted.

🗂️ ‘South Korea’s Adopted Children’

— Anadolu English (@anadoluagency) February 10, 2025

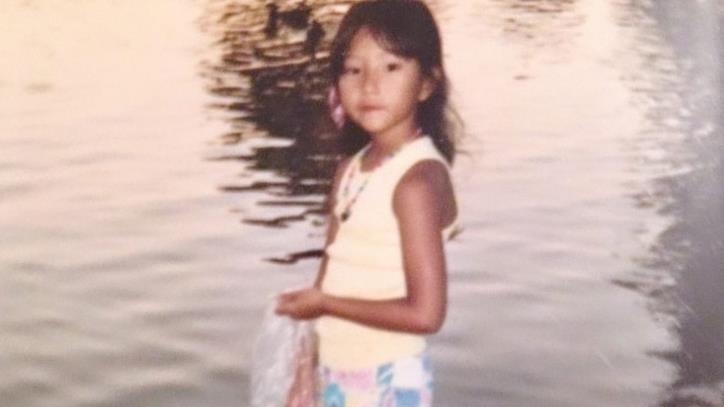

▪️After the Korean War, economic difficulties led to the adoption of over 200,000 children, around 150,000 of them by American families

▪️Koreans trying to reunite with their biological families share their struggles and views on adoption… pic.twitter.com/uo4tfk3Nw4

He emphasized the importance of the US Citizenship Act passed in 2000. However, Amanda Cho, Policy Manager at Adoptees For Justice, pointed out that the law does not cover individuals born before 1983. Many adoptees only discover they are not US citizens during legal proceedings, such as criminal cases or court hearings. Some are expelled from the country for 10 years, while others face lifetime bans.

Cho highlighted a troubling reality: some deported adoptees have been rejected by the South Korean government. “We know that some adoptees sent back to Korea were told, ‘No, you are not recognized here.’ I don’t know if any other country has responded this way, but we are trying to support those Korea has turned away. Right now, they have no country,” she said.

South Korea’s longstanding adoption program

According to researcher Kim Park Nelson, South Korea’s international adoption policies stand out because of their longevity. While other nations with similar programs eventually phased them out, South Korea’s adoption system has been in place for nearly 70 years.

Park Nelson noted that in recent years, international adoptions from South Korea have declined due to women gaining greater social and economic equality. However, she stressed that intercountry adoption is not an issue unique to South Korea.

“Because Korea has sent so many children abroad, people sometimes ask, ‘What is Korea’s problem?’ But that’s not the right question. It’s not that South Korea itself is the issue, these adoption systems exist in many countries, including the US. The real question is: What is wrong with the systems that lead to children being sent away in the first place?” Park Nelson explained.

The challenge of integrating into a country you didn’t grow up in

Kim Park Nelson, a researcher specializing in the social integration of returned adoptees in South Korea, explains that most adoptees struggle to see themselves as part of South Korean society. Having grown up in another country, they often feel disconnected from the culture and language.

“It is incredibly difficult to fully integrate into a country where you are neither a citizen nor have spent your formative years,” Park Nelson said. “You don’t share the cultural background or language of that country.”

Amanda Cho echoed the sentiment, reflecting on her own experience. “When we were adopted in the 1970s, my parents were told to assimilate us into American culture. Growing up, I thought of myself as Italian because my father was Italian, and my mother was of German and Irish descent. I didn’t see myself as Asian or Korean at all -- I thought I was from those backgrounds.”

Jane Jeong Trenka, another adoptee, shared a similar struggle after moving to South Korea. “I live here as a foreigner. I don’t belong anywhere,” she said.

For adoptees whose biological families cannot be located, the sense of displacement can be even deeper. Trenka added, “You can completely erase their names and identities. This happened to me.”

Strict adoption criteria in the US, South Korea

In a statement to Anadolu, the US State Department reaffirmed its commitment to ensuring that intercountry adoption remains an accessible option for children in need of permanent families.

It emphasized that measures have been implemented to ensure adoptions are conducted in a “safe, ethical, legal, and transparent” manner. Adoption agencies must meet strict criteria, ensuring that the process aligns with the laws of the US and South Korea.

To strengthen oversight, officials from the State Department’s Office of Children’s Issues (CI) traveled to South Korea last June. They met representatives from the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Truth and Reconciliation Committee to discuss adoption policies.

South Korea’s efforts to reduce intercountry adoptions

South Korea has recently adopted a more selective approach to intercountry adoptions. Cho noted that new regulations prioritize keeping adoptees connected to their Korean heritage.

“A while ago, South Korea introduced a rule stating that only South Koreans or people of South Korean descent could adopt children abroad. There’s also a requirement that at least one adoptive parent must travel to Korea, stay for a period, and learn about the culture,” she explained. “Now, the government is ensuring that adoptees maintain some connection to Korea.”

Further reinforcing this shift, the South Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare announced last May that a new law would take effect this year, mandating that central and local governments assume full responsibility for the adoption process.

According to the ministry’s statement, the revised system aims to reduce intercountry adoptions by prioritizing domestic placements for orphaned children within South Korea.

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.