ANKARA

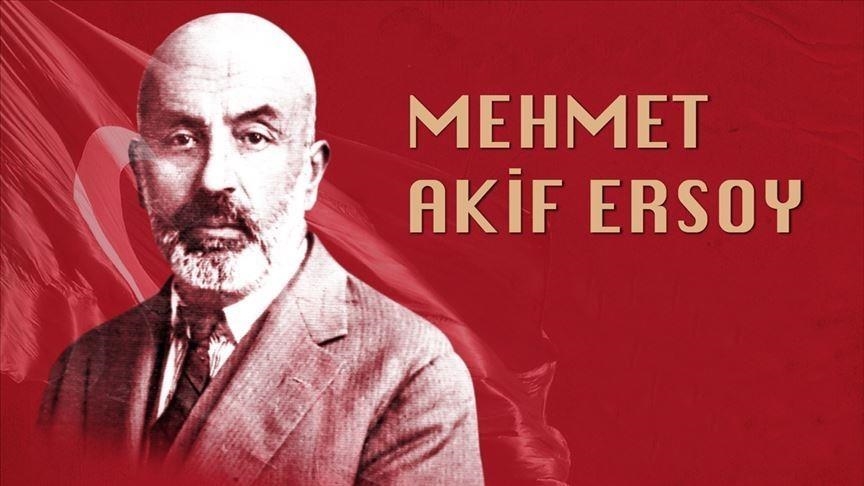

Mehmet Akif Ersoy rightfully occupies a unique place in the hearts of millions of Turks as the poet of the national anthem, Istiklal Marsi, or The Independence March.

But it is essential to remember the other qualities that allowed him to gain a special place in Turkish history.

He was born on Dec. 20, 1873 in the Fatih district of Ottoman Istanbul. Akif attended primary schools and secondary school in his district.

In addition to French, he was taught in public schools and learned Arabic from his father, Tahir Efendi, a lecturer at the Fatih madrasa, and improved his Persian in general courses at mosques.

Following his graduation from secondary school, he registered in the high school section of the School of Political Science (Mekteb-i Mulkiye).

Even though he completed the three-year first section of the school in 1889, he had to leave when his father’s death compelled him to find a job to support his family.

That same year, he registered at the newly founded four-year Civilian Veterinary School (Mulkiye Baytar Mektebi), from which he graduated with high honors.

After graduation, Akif was appointed a deputy inspector by the Ministry of Agriculture. While this job allowed him to experience county life in the vast Ottoman domain, from the Balkans to the Arabian Peninsula, his idealism and passion for education made him teach veterinary sciences in state agricultural schools and literature at Istanbul University.

Standing out as a patriotic orator and man of letters, Akif was recruited into the Ottoman intelligence service (Teskilat-i Mahsusa).

In 1915, he was sent to Germany to report on the Muslim soldiers of Allied Forces captured by Germany. Later, he was posted to Arabia to counter British propaganda among Arab tribes that urged them to revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

Akif neither lost his optimism nor patriotism when the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in WWI led to its occupation by the British, French, Italian, and Greek forces from the fall of 1918 onwards.

From the early stage of the Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923), he made a significant contribution to moralize and mobilize Turks by delivering speeches in mosques across Anatolia -- the most famous at the Balikesir’s Zaganos Pasa and Kastamonu’s Nasrullah mosques.

He published the speeches and many other pieces supporting the resistance against the occupation in the Sebilurresat periodical.

While he came under strict surveillance and pressure from occupation authorities, Akif, upon invitation from Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the leader of the resistance, moved to Ankara shortly after the establishment of the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TGNA) on April 23, 1920.

He joined parliament as a deputy of the southwestern province of Burdur.

Meanwhile, Akif traveled across Anatolia to boost morale and enlist support for the resistance, which he regarded as a religious and patriotic duty.

The Ministry of Education in Ankara launched a competition for a new national anthem in November 1920 to which more than 700 poets were sent. Initially, Akif did not participate as a money reward was attached.

Eventually, he was convinced to participate by the Minister of Education Hamdullah Suphi Tanriover, also a man of letters.

Akif wrote Istiklal Marsi, which was read in the Grand National Assembly by the minister on March 1, 1921, and unanimously accepted as the Turkish National Anthem on March 12, 1921.

When the Republic of Turkey was proclaimed in 1923 as a result of the victory against occupying powers, Akif, as a believer of pan-Islamism, grew frustrated with the secular character of the new state and eventually moved in 1925 to Egypt, where he taught Turkish at the University of Cairo and continued writing and translating undertakings.

In 1935, he caught malaria on a visit to Lebanon and moved back to Turkey the following year, shortly before he died Dec. 27, 1936.

Apart from the Istiklal Marsi, he is best known for his 1911 work, Safahat -- a collection of 44 poems of various lengths.

The earliest work that appears in the book is dated 1904, but is unattested, and it is highly likely that the poet, who was 32 at the time, composed poems before that date

Akif avidly read Turkish, Arabic and Persian literary classics. His favorites in these three languages were Fuzuli, Ibn Farid and Saadi Shirazi, respectively.

He was particularly an admirer of Shirazi, whom he considered the quintessence of the “wisdom of the East” and whose influence he always admitted. From 1898, he serialized the translation of selected texts from the Persian classics in the periodical Servet-i Funun.

From Western literature, he read, in French, the works of Lamartine, Victor Hugo, Emile Zola, Ernest Renan, Alexandre Dumas, among others.