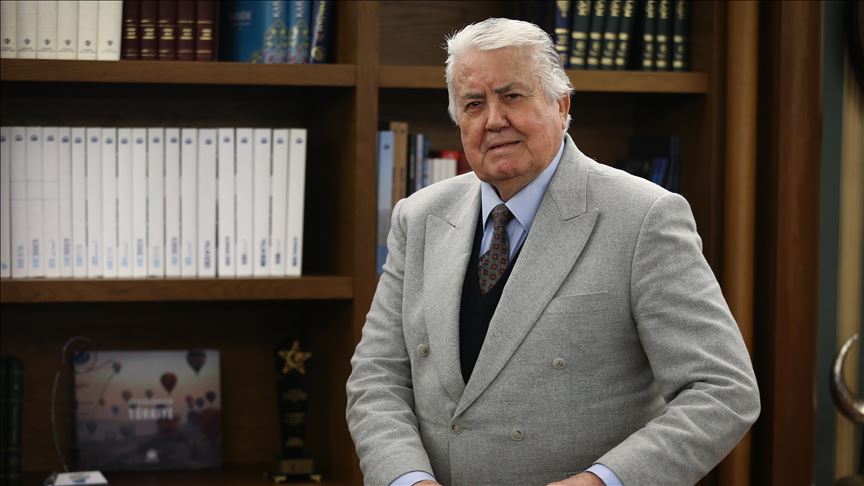

World-renowned Assyriologist Veysel Donbaz

World-renowned Assyriologist Veysel Donbaz

ANKARA

A Turkish expert on ancient Mesopotamia has dedicated more than half a century of his life to unearth history, culture and language dating back to over five millennia in the cradle of civilization.

In an exclusive interview with Anadolu Agency, Assyriologist Veysel Donbaz shined light on the ancient languages of Sumerian, Akkadian and Hittite -- used to be spoken across modern day’s Turkey and Middle East -- as well as the clay tablets that carried these extinct tongues into modernity.

Anadolu Agency: What is an extinct language?

Veysel Donbaz: The extinct languages are no longer used by people at all but translations of which were written before. A written source is obligatory to define them as extinct.

There are nearly 200 extinct languages to this day that were discovered.

No one can speak these languages, that is why they are called extinct languages. Who is going to verify these languages? There is no one from ancient eras. If similar expressions are written, we can take it from there. So, we're translating what was written before.

Many countries around Turkey use a different alphabet than Latin letters, countries like Iran, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Russia, Bulgaria and Greece. All European languages use the Latin letters. The same happened with cuneiform scripts in ancient history.

AA: What are some features of the Sumerian language?

Donbaz: Sumerians brought their cuneiform scripts around 3500 B.C. or were told to invent their language there.

The Sumerian language is monosyllabic and, as in Arabic and other some modern tongues, distinguishes between masculine and feminine words.

It does not have an alphabet. It used syllabic writing in Sumerian ideograms. If a word is used in a sentence, it becomes a syllable. When used alone, it becomes a concept. Therefore, in order to understand a sentence in Sumerian, the meaning of every syllable needs to be known.

Also, it used a determinative before every word to make it simpler. If you use the word “tok” before a word, then you will know that “tok” describes something related to the word dress in Sumerian ideograms.

AA: Could you tell us about the roots of ancient Mesopotamian languages?

Donbaz: During ancient era, the languages of Sumerian and Akkadian were used in Mesopotamian civilizations.

Akkadian language -- which belongs to Semitic Languages Family -- has two most important dialects, namely Assyrian and Babylonian.

Akkad is a state. Sargon of Akkad united the citystates and formed the Akkadian Empire in 24 B.C., but did not overshadow Sumerian language and translated them into Akkadian language.

AA: How are ancient languages studied in Turkey?

Donbaz: Turkish Historical Society was founded in 1931 upon Mustafa Kemal Ataturk's orders, modern Turkey's founding father, and 23 different language departments opened during late Education Minister Resit Galip's tenure, including Hittite and Sumerian.

In Turkey, there is a department of sumerology at Ankara University’s Faculty of Language, History and Geography.

In Turkey, if one is working on Hittite languages, it is called hittitologist. Turkish scholars have divided it into Sumerian and Hittite.

In foreign countries, they were described as an “assyriologist”. The field of assyriology includes both the Sumerian and Akkadian languages. Hittite language was studied separately abroad.

Assyrian is a dialect of the Akkadian language. Sumerologist would be a better title in Turkish.

AA: How many words in modern Turkish do come from these extinct tongues?

Donbaz: Many Turkish words used today, against the common thought, come not from Arabic or Persian, but from Akkadian. The Turkish names of seven months out of 12 come from Babylonian. There are more than 100 words that were transformed into Turkish from Assyrian and Babylonian languages, but there are nearly no words except a few which came from Sumerian languages to Turkish.

For example, the word in Turkish “ekalliyet” [minority] is rooted in Assyrian and Babylonian dialects as “egallum”.

The names also have meanings. If one becomes a father, he always says “Iliddin”, meaning “God Given” [Allahverdi in Turkish]. And, also the word “Ilbani”. Ilum means divinity. Ilbani means, “to do”. In all it means “God is the creator”. Turkish use these words in its language, too.

However, it is impossible to prove that Turks come from Sumerians or Sumerian people were Turks.

Apart from lingual traces from the era, the modern seven-day week and 30-day month are also the product of ancient Mesopotamian civilization.

AA: You know multiple ancient and now-extinct languages. Could you tell us a little bit about these?

Donbaz: I know three such languages: Sumerian, Akkadian and Hittite. One would also need to know the development of these tongues through time. [Assyrian] changes through Old Assyrian, Middle Assyrian and New Assyrian. I know all of these, though not all [scholars] do. I have to know all of them. Some only learn Assyrian, and are unable to read older texts. Over a thousand years pass between these timeframes. As a curator of an archive, the manager brings you a wide range of tablets which you must study and learn. I learned many of them on my own while working at the museum. A person must educate oneself, this how you become a master.

AA: Today, can anyone gain access to these tablets as you have?

Donbaz: The tablets are soft [since] they were not baked at the time. They are soluble in water, and can be turned into mud. There are two separate words, one referring to dissolving tablets in water and the other to breaking them.

Nearly 25,000-30,000 tablets have been excavated from Kultepe or Karahoyuk -- roughly 18 kilometers (11 miles) from Kayseri [southern Turkey today]. These weren’t dissolved in water or broken, [the information on them] having expired, though. These began to be dug up after they were discovered in a seasonal dig in 1925.

We organize a biannual symposium there with foreigners [experts]. I went to the first two. Tablets are not found there anymore. Around 25,000-30,000 tablets were excavated from that site.

AA: Can these tablets be preserved? If so, how is this done?

Donbaz: The tablets can be preserved. They are written without ever baking [of the clay]. This is a kind of local clay that does not crack. In fact, some amount of chamotte is added to it to keep the clay together.

We have 19 collections. Out of total 41,000, some 14,000 were excavated from Nippur. Other sites gave us 5,000, 4,000, 3,000, 1,000 [tablets]. Some collections even contain 17 tablets, and we have two tablets from the Urartu. In total, we have 73,000 tablets.

None of these tablets were baked. They were usually stored in palaces or temples. These were the documents used to keep official records.

There is a place called Sapinuva in Corum [northern Turkey] where around 3,000 tablets were unearthed. Another place was excavated in Sivas. Some 60-70 tablets were discovered there, as well.

These were akin to the official [records] and publications of today. Luckily, they [Hittites] had written them down on clay. When one state fell, [its conqueror] would come and preserve these records itself. Other times fires would break out, which would sometimes bake the tablets.

If a tablet is black, that means there are still gases trapped within it. If testaceous, that means it’s been baked red-hot. In that case, there is no danger in placing it in water.

We would bake the tablets that we found in special furnaces. When I came to the site in 1962, this process took a year. They must initially be baked at 110 degrees [Celsius] (230 degrees Fahrenheit) for 24 hours to vaporize their moisture. If this goes up to even 115 degrees [Celsius] (239 degrees Fahrenheit) the tablet will burst. We know this because we tried it on new tablets. You also mustn’t exceed the time, even by a minute.

After this, one would have to put a tablet in an oven at 450 degrees [Celsius] (842 degrees Fahrenheit) to release the gases trapped within it for six hours. It would then be baked for an additional six hours at 750 degrees [Celsius] [1,382 degrees Fahrenheit]. At this point, the tablet changes biologically. It solidifies. After that, the tablet is left under running water for a month to get rid of its salts which can damage the tablet.

Some very small flies can also reside in some tablets. We place such tablets in cupboards within cotton-filled boxes with glass tops so we can see what is inside. These cupboards must be made of natural wood and the air shouldn’t be humid, otherwise these flies will harm the tablets. If they are placed within metal boxes or preserved in a humid climate, the tablets will disintegrate. Even light damages them. In order to treat against flies, we hold the tablets within smoke once a year for 24 hours. The temperature must be 23 degrees [Celsius] (73.4 degrees Fahrenheit) and the humidity should be at 57. We keep a dehumidifier working in the room at all times to keep the moisture in the air constant.

After this process, we record the tablets in a list, one-by-one. Aside from my academic research, I made the list of some 35,000 tablets. We photographed them, and dated them where possible. This made their contents clear. For instance, there was a man who had left his city on travels. He was given a small tablet as a travel permit. This showed what he was carrying: Onions, white cheese, milk.

They would give the firmest onions to their highest-ranked men, so that you would know that this man was important by the smell on his breath.

AA: Could you share some interesting facts or passages you came across in all of those tablets you read?

Donbaz: According to tablets recording what messengers, or "lasime", carried with them as food, we can discern that they took 22 kernels of grain to be equal to a gram, while they took 180 as equal to a "sey’um", which was their counterpart to the 8.5-gram weight that the Hebrews called "shekel", also known as "mina", or "mana". When multiplied 60 times, it became one "diltum", "kalent" or "yanduk", roughly half a kilogram [1.1 pounds].

The tablets were sealed when they were being brought to Asur which took entrance fees and fees for the feet and head of the traveler, and an additional fee if they were traders. They were unsealed only at the palace, in Kayseri.

There would a bag to carry food and drink for both a master and a beast during the voyages. These were called "eliatums". Tin was called "hent tin" when it was used as currency in trade, while gold was used as investment, much like it is today.

Some of these civilizations used a currency system almost identical to Gold Standard which was used in modern times [until 1970s], as well.

They used a seven-day week, a 24-hour day and a 30-day month -- they didn’t have 31-day months, though. They used a lunar calendar with a year of 354 days. Their interest rates were set at 33 percent, they had government bonds, etc. They knew of all of these things. There are thousands of tablets on these things.

There was also an interesting treaty between the Assyrians and the Hittites. On a 91-line tablet, the sides agreed at Kultepe that it would be the Assyrians that would try cases when person was killed by accident in Anatolia. Kultepe, also known as Neysa in the old Hittite times, was home to the Assyrian trading tribes.

It also forbade smuggling by the Hittites, and stipulated the payment of four or five duties to the Assyrians on pain of imprisonment. [On the other hand,] if bandits were to steal the goods of a trader in Anatolia, authorities would first search for these goods, and recompense the trader if they couldn’t be found.

Hittites were barred from taking a good-looking slave girl or a good animal, etc. they owned back to their own country or sell them to their people.

However, when negotiating this agreement, the Assyrians did not refer to their ruler as "king", but as "vatlum", meaning guild master. They did this so the Hittite king would not take offense. They made treaties against smuggling.

In wedding vows, they used phrases similar to those we use today. For example, they would ask the bride: "Do you accept to remain loyal to your husband?" They would also say: "riches owned by either side now belong to both. They will support each other in goods and in bad."

Writing by Ahmet Salih Alacacı,Faruk Zorlu

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.