Austria’s ban on Muslim Brotherhood symbols has further aims

At the backdrop of an attempt to minimize the role of civil society organizations, Austrian Muslim organizations seem to function as a playground for implementing more authoritarian policies

SALZBURG

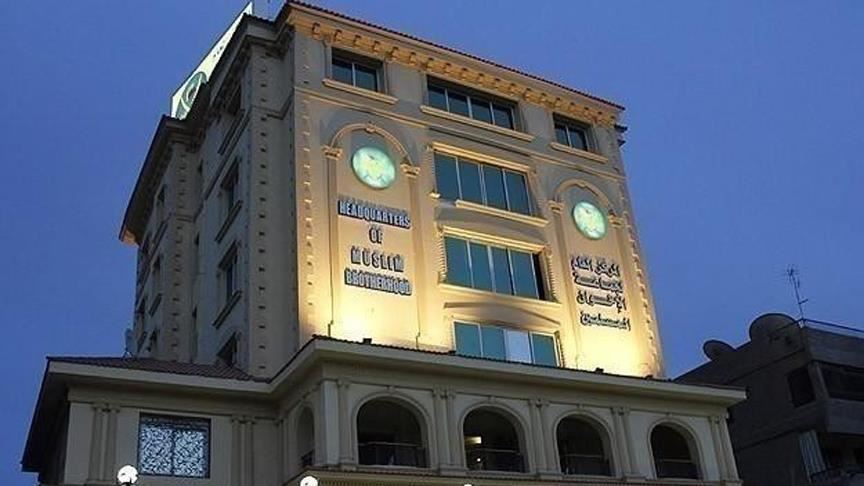

On March 1, 2019 something unprecedented took place in a Western country and it has gone nearly unnoticed. The logo of the Muslim Brotherhood, along with logos of other non-terrorist and terrorist organizations, was added to the list of symbols banned in Austria. In many countries, right-wing groups and lobbies have long been trying to have the Muslim Brotherhood banned. Many observers argue, however, that the real goal of these efforts is not to threaten the Muslims Brotherhood, which is already weak and politically defeated in many Arab countries, but actually to threaten civil society activists and politicians with a Muslim background in the West.

People who make a difference, such as the newly elected U.S. Congress women Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, as well as political activists such as Linda Sarsour, have been repeatedly targeted by the far-right, which speaks of these figures as belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood. In the U.S., there have been three legislative attempts to implement a bill to declare the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization. As rightly criticized by civil society, this would in fact not primarily hit the Muslim Brotherhood itself, but rather American Muslim associations that do social justice work and are an important voice of nonviolent political opposition to injustice and racism.

As the Network Against Islamophobia (NAI), a project of the Jewish Voice for Peace, argued, the Trump administration could easily “use this legislation and an executive order to target national and local Muslim civil liberties and other organizations that work on behalf of Muslim communities.” In the U.S., the so called “Muslim Brotherhood Terrorist Designation Act of 2017” was not enacted due to foreign policy considerations. But similar attempts can be seen in other places. In April 2014, the British prime minister of the time commissioned an internal review of the Muslim Brotherhood to determine whether or not it was possible to associate the organization in the UK and abroad with extremism and terrorism. The report led neither to a ban of the Muslim Brotherhood, nor to its designation as a terrorist organization.

Austria has thus been the first country to designate the Brotherhood as an extremist organization. This could only happen at the backdrop of a legislation prepared long beforehand. After World War II, Austria outlawed symbols of National Socialism by issuing the Prohibition Act of 1947. Decades afterwards, following the rise of Daesh, a coalition government formed by the conservative ÖVP and the Social Democrats outlawed the use of symbols associated with Al-Qaeda and Daesh in 2014. The Symbol Act of 2019 was enacted this year in March by a right-wing government composed of the right-wing extremist Freedom Party and the restructured People’s Party headed by Sebastian Kurz. It extended the ban to the PKK, Hamas, the military wing of Hezbollah, the Muslim Brotherhood, the Turkish nationalist “Grey Wolves”, the Croatian fascist Ustashe, and organizations designated as terrorist by EU legal acts. The government claims that “the symbols and gestures of the organizations mentioned in the amended law are against the constitution and contradict our basic democratic values.”

While terrorist and non-terrorist organizations are included in this new list, white extremist organizations with many links to the governing FPÖ, such as the Identitarian Movement, are not mentioned in this act at all. But most importantly, the legislation allows the minister of interior to expand this list to include other groups with a decree at any time. This enables the minister to potentially crack down on any “foreign” civil society organization that protests the government and is considered a threat to the government. With this warrant, the minister of interior (currently from the FPÖ) can potentially go after every oppositional Muslim organization.

The official interpretation of the law by the lawmakers has already revealed in the case of the banning of Muslim Brotherhood symbols that it is not targeting the Muslim Brotherhood itself, but rather those Muslim civil society organizations that criticize the government for its anti-Muslim policies. The interpretation widely drew on a report written by a central figure in the anti-Muslim think tank world, Lorenzo Vidino, whose fellows at the European Foundation for Democracy systematically target the most vocal Muslim civil society organizations across Europe with the aim of criminalizing and subsequently excluding them from the public sphere. In the “The Muslim Brotherhood in Austria” report, which was drafted for the Ministry of Interior, a link was made between numerous Muslim people active in civil society, who are well-known in the Austrian society.

The government has already declared that it will implement a new legislation in an attempt to crack down on what it calls “political Islam” in summer 2019. At the backdrop of an attempt to minimize the role of civil society organizations in Austrian political life, Austrian Muslim organizations seem to function as a playground for implementing more authoritarian policies.

More importantly, this legislation will not remain limited to Austria. As a long-time member of the European Union (EU) with a stable economy and a still well-working social system, its anti-Muslim legislations have become models for other right-wing parties to imitate. German politicians from the center-right as well as politicians from the eastern part of the EU often draw on the Austrian experience in implementing anti-Muslim legislation, from the Face Veil Ban Act of 2017 to the Islam Act of 2015. The Symbol Act could be yet another example for “transatlantic learning”.

- Farid Hafez is a senior research scholar at the Bridge Initiative at Georgetown University and a senior researcher at Salzburg University.

* Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Anadolu Agency.

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.