PARIS

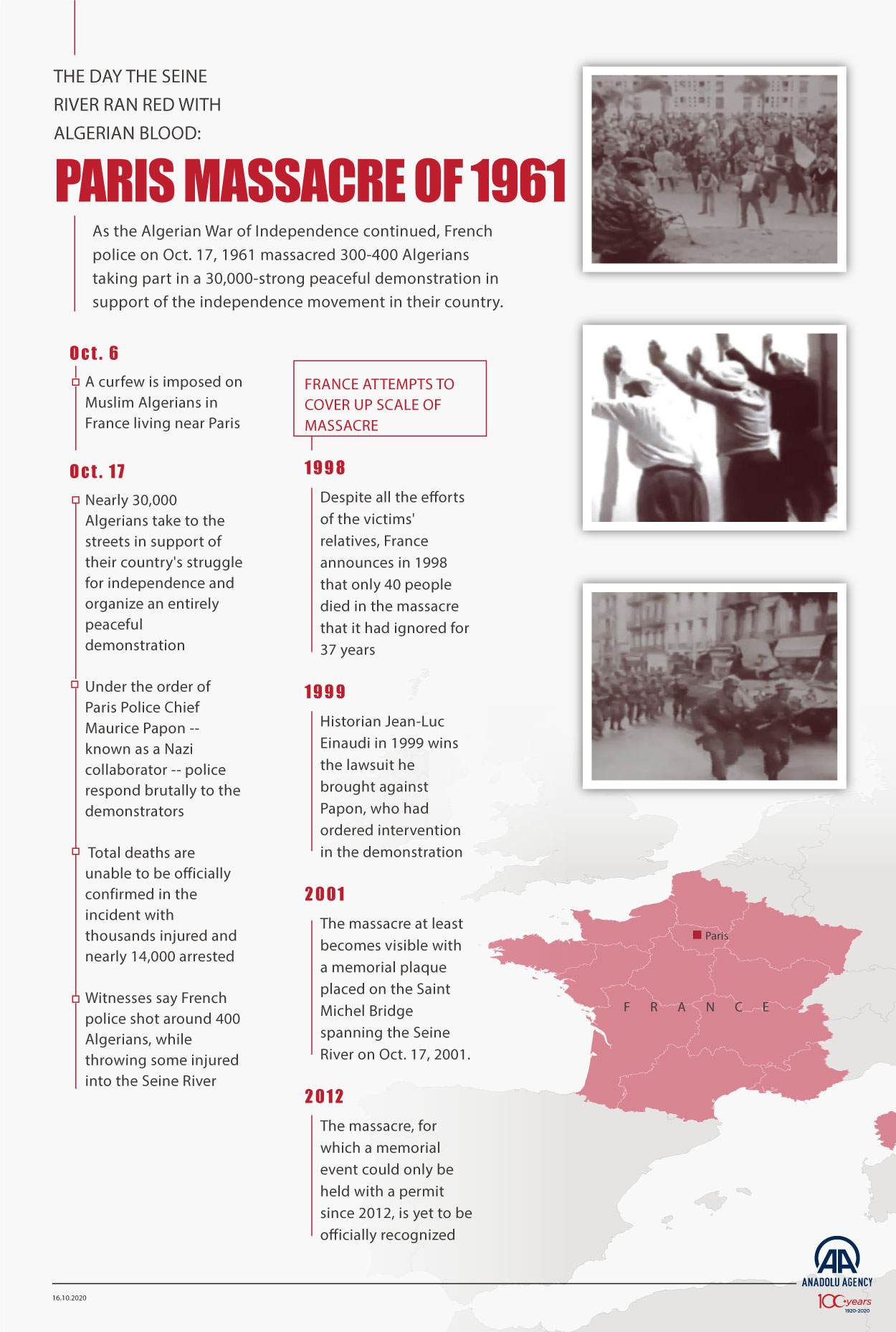

The memory of the 1961 Paris massacre, when as many as 400 demonstrators were killed and thrown into the Seine River for supporting the Algerian War of Independence, is still alive after 59 years.

Despite efforts by the victims' relatives, France tried to hide the scale of the massacre for 37 years and announced in 1998 that only 40 people were killed in the protests.

Forty years after the massacre, the Paris mayor erected a plaque on Oct. 17, 2001, on Pont Saint-Michel in remembrance of the massacre.

A curfew was imposed on Muslim Algerians living in and around Paris on Oct. 6, 1961.

Nearly 30,000 Algerians, who took to the streets Oct. 17 to support the struggle for independence, organized a peaceful demonstration but police attacked demonstrators under orders from the head of Parisian police, Maurice Papon.

Papon was known for his activities during World War II when he participated in the deportation of more than 1,600 Jews. He also served the Constantinois department in Algeria during the Algerian Independence War and later become the head of Paris police.

Thousands of people were injured and 14,000 were detained during protests. Although no official death toll was announced, witnesses suggested nearly 400 Algerians were shot by police and some with injuries were thrown into the River Seine.

Witnesses reported that demonstrators were also killed in the garden of Paris police headquarters or subway stations.

After France announced in 1998 that only 40 people died in demonstrations, historian Jean-Luc Einaudi won a case filed in 1999 against Papon, who ordered intervention in the demonstration.

Even though it became official that the massacre was intentional, the incident is still treated as taboo by official institutions and administrators in France.

Anadolu Agency’s request for access to archives about the massacre on its 59th anniversary was declined by the Paris Police Department and the Department of Memory and Cultural Affairs, citing COVID-19 restrictions.

Protestors did not even carry a pocket knife’

Ait Ouazzou Areski, 84, who was one of the pioneers of the Algerian Independence Movement (FLN) in France and the Oct. 17 demonstration, personally witnessed the incident and spoke exclusively to Anadolu Agency about the before and after the massacre.

Areski, who was imprisoned for years, said the demonstration was organized to protest the Oct. 6 curfew by "racist" Police Director Papon who was brought to power by the French administration.

He said, the prime minister at the time used the curfew to sabotage negotiations between France and the FLN. “It was a discriminatory, arbitrary curfew targeting only people of Algerian descent," he said.

Areski said that people of all ages participated in the demonstrations, which was called by the FLN. "I did a body search myself, the demonstrators did not carry even a small pocket knife."

Nearly 80,000 Algerians of all ages, men and women, participated in the demonstration, according to Areski, who said police began firing automatic weapons at close range at tens of thousands of protesters who filled the streets.

"A large number of people fell to the ground like potato sacks, the police picked up those that fell on the ground with trucks and threw them into the Seine River. Paris has never witnessed such a massacre before. Even during the Second World War, there was no massacre like this," he said. “We want France to recognize its crimes and massacres of its colonial past and make amends.”

Biggest massacre since World War II

Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, professor of political science at the Evry-Val d'Essonne University, told Anadolu Agency that Papon was acting in revenge and brought “torture, extermination, extrajudicial execution” to Paris.

“On Oct. 17, 1961, the biggest massacre since World War II happened in Paris upon the orders of Maurice Papon,” he said.

“The Paris police chief did not act independently from his superior, the Minister of the Interior, Prime Minister and then-French President General Charles De Gaulle. Together with the lawyers, we consider this a state crime. The massacre of Oct. 17, 1961, constitutes a crime against humanity because it has a political, racist, and even religious aspect,” said Grandmaison.

He said Paris held memorials every year for the massacre but it is not enough. Some statements were made by officials but the highest ranks of the state have not recognized the crime which was deliberately committed.

The crime was committed not only in Algeria but also in France, said Grandmaison, noting it shattered the republican myth that colonial crimes were only committed in foreign colonies.

Grandmaison said when the massacre took place, it was ignored not only by French media, but by activist groups of the time, workers' organizations.

France struggles to face its colonial past

Karima Direche, director of the Institute for Research on the Contemporary Maghreb, said France is struggling to face its colonial past.

“Real bullets were used against unarmed demonstrators. Thousands of Algerians were detained and sent to prison. They were subjected to abuse. Dozens of people died. Some people were killed by bullets. Some people drowned as a result of being thrown into the Seine River. Disproportionate pressure and force were used by the French security forces,” she said.

Direche said authorities thought the pressure on Algerians was legitimate and although former President Francois Hollande made a statement remembering the massacre, he failed to recognize France’s responsibility.

“The French state is struggling to confront its colonial past. Colonialism is a part of French history,” she said. “The French state did not fully accept its responsibility in this massacre. There has not been a political statement about the responsibility of the French state.”

Not only state crime, but also social memory loss

Yasser Louati, head of the Justice and Liberties For All Committee, said the massacre happened because Papon could not stand to hear the voice of liberty in Paris.

Louati said Papon was a member of the Vichy Government, which sent thousands of Jews to concentration camps, before he became police chief and was not prosecuted for his crimes.

Stating that Papon continues its old habits with Algerians, Louati said the French administration is a partner in crimes by keeping Papon in office.

“No institution opposed Papon for its decisions. Years have passed since the massacre and it was never mentioned, until the 1980s. Back then, historians like Jean-Luc Einaudi did their job and documented this bloody massacre,” he said.

Louati said France does not reckon with its past and no president has apologized for what has been done. The massacre is still taboo and is not thought in schools.

"The 1961 Paris Massacre is not an event recognized as a bloody act in the history of the republic. There is a desire to forget or underestimate what happened in October 1961," he said.

Louati said the government of President Emmanuel Macron pressured associations trying to bring the massacre to the agenda under the pretext of "fighting Islamic separatism."

“This shows that we are in a France that persecutes those who want to remember and remind the past,” he said.

“This massacre deserves a national attribution, a day of remembrance, an official speech from the president, because it took place in the heart of Paris, not in a distant province. It was a decision taken on behalf of the French state, and different government agencies did nothing to prevent the incident,” he said.

*Writing by Busra Nur Bilgic Cakmak

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.