Rohingya's relentless struggle to overcome barriers to education

Community leaders say they want to ensure fundamental right of education for stateless refugees

DHAKA, Bangladesh

Saifullah Muhammad, a Rohingya youth, is currently working full-time as a community builder in Canada while also pursuing his master’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Waterloo.

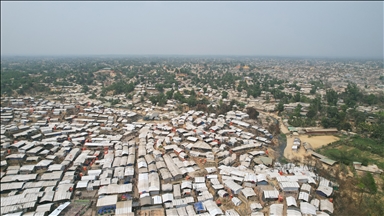

Growing up in congested refugee camps in Bangladesh's southern district of Cox's Bazar as a member of a man-made stateless community, Muhammad's long journey to his current state is a tale full of struggle, barriers, and plights.

"When my classmates' parents came to visit them in school and college with gifts, I occasionally sneaked into the camps to secretly visit my parents for a short while," he recalled sadly.

“Through a huge challenge, I managed to come out of the camps and get into a high school, and continued my studies until I got admission for an honors degree in Bangladesh,” Muhammad told Anadolu Agency.

"I was lucky to have the opportunity to get an education, an honor which was denied to so many, particularly Rohingya children at the time," he said.

"If it had not been for the rare educational opportunities in Bangladeshi schools, I do not know how I could have made it here," he said, adding that "schooling afforded me the privilege in 2006 to make my way beyond the meager horizon of the refugee camp. I'm thankful for the scholarship that allowed me to set foot at Chiang Mai University in northern Thailand. I was among the rare and fortunate ones."

He said he tried his best to remain focused on his mission of bringing light to what was happening to his community while advancing his studies.

"Unfortunately, it didn’t go as smoothly as we had hoped. I had to move to Malaysia," he added. Muhammad had to work hard for his survival while in Malaysia.

"Every time I talked to my parents, I was worried about the misery they kept hidden from me, the stories of shame and indignity they shielded from me," he sobbed, not hiding his anguish.

"Despite the fact that I now live in a stable country with every privilege, I’m still shamefully indebted to them here," he added.

More than three decades ago, in 1991, Muhammad fled a cycle of persecution in his home of Myanmar’s Rakhine state with his parents and took shelter in Bangladesh, which is now home to nearly 1.2 million Rohingya Muslims, most of whom escaped a brutal military crackdown in August 2017.

“Many of my community members were forced to return either to Myanmar or to Bangladesh on legal grounds, but luckily I was registered by the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, and somehow escaped the drive,” he said, adding that finally, luck favored him to fly to Canada in 2016.

This is Muhammad's short story, in which he has barely spent any sweet days with his family and yet wants to serve the community members from afar.

Even the lucrative country of Canada, a dream destination for millions, cannot quench his thirst to support the stateless Rohingya because his parents are still living in crammed tents made of bamboo and tarpaulin sheets in Bangladesh.

Ignoring education

Mohammad Hamidullah, a Rohingya youth who was a secondary school student when he fled the August 2017 military clampdown in Rakhine and has been living in Bangladesh's camps, told Anadolu Agency that world leaders have done a lot for them but are ignoring the issue of education.

"We’re almost confined within the camps, and we have no access to higher education," Hamidullah noted, adding that the host country's authorities have also imposed new restrictions.

On Dec. 18, Human Rights Watch called on the Bangladeshi government to “urgently reverse a decision to close thousands of home-based and community-led schools for Rohingya refugee students.”

If Bangladesh does not repeal the move, “approximately 30,000 (Rohingya) children will lose their access to education,” said a statement.

In a notice issued on Dec. 13, the government said all private learning centers in the Rohingya camps “must be shut down.”

Mohammad Hossain (original name withheld for his safety), a Rohingya youth who recently graduated from a Bangladeshi university, told Anadolu Agency that he will not apply for any jobs in the host country.

“My target is to migrate to any third country so that I can study more, get a good job, and work for my community. It’s risky to apply for any job here as I might get in trouble during the police verification,” Hossain added.

Online higher education

Dr. Ambia Parveen, head of the European Rohingya Council and also a noted physician at a German hospital, told Anadolu Agency that education is not a “luxury," but rather a fundamental right of every human being regardless of religious belief or political association.

Parveen was detained by the Myanmar military junta in 1981, along with her mother and sisters, after the junta failed to locate her father, a chemical engineer in Yangon.

"My father was fired from his government job simply because of our Rohingya ethnicity, and then he escaped to Bangladesh out of fear that the military junta might persecute him even more," she explained, adding that due to his quick decision to relocate to a secure place, he was unable to bring his family with him.

"As my father had forewarned, the military stormed our house and arrested us and our mother when we were children," she recalled.

"After a month, we were released and were able to flee the country and reach Bangladesh. We subsequently relocated to Germany, where I’ve been for the past 16 years," she said, adding that she also has two sisters who are also doctors.

She stressed that educated people are an asset to the entire world, saying that if nearly 10,000 Rohingya youths in Bangladeshi camps receive higher education, "they can bring huge benefits for them, for families, and for the entire globe."

"Education is the transmission of your culture and values to the next generation. Unfortunately, we Rohingya are failing to adorn our history through this human necessity," she explained.

Mentioning Dr. Anita Schug, the first neurosurgeon in Rohingya history, who is now settled in Switzerland, Parveen added that if the huge Rohingya population is deprived of education, they may be influenced to commit crimes and become victims of human trafficking.

She urged the international community and Bangladesh to provide online higher education opportunities for Rohingya people. "The developed nations then choose the most deserving and can provide scholarships to them."

According to Parveen, simply providing food and shelter will never be enough to ensure a nation's dignity.

AK Abdul Momen, Bangladesh’s foreign minister, told Anadolu Agency that many developed nations have large tracts of unused lands and that they can also shelter some Rohingya in their own territories. “It’s not fair to always put the burden on Bangladesh,” he added.

Shutting only some private coaching centers

Speaking to Anadolu Agency, Bangladesh Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner Shah Rezwan Hayat said that no camp-based learning centers being operated for Rohingya children have been closed.

“We’ve directed just to shut only some private coaching centers where Rohingya children were taught the Bangla language and also there are allegations of spreading radicalism against those coaching centers,” he said.

He added that there are nearly 3,000 camp-based learning centers run by various NGOs and other agencies inside the camps with due permission from Bangladesh, and that a huge number of Rohingya children have been being taught there under Myanmar’s curriculum so that after peaceful and dignified repatriation they can continue education in their home country.

“If Rohingya children are taught the Bangla language, violating the rules of Bangladesh’s government, there is a risk that many Rohingya students will be mixed in with the local community,” Hayat warned.

Moreover, he argued, if such unauthorized coaching centers are being operated, Rohingya children will lose interest in already functioning learning centers, and already there are reports of dropouts from the main learning centers. “This will hamper the overall education system for Rohingya in Bangladesh camps,” he said.

Hayat also said that a pilot program to teach more Rohingya children in collaboration with UNICEF under Myanmar’s curriculum is in the works.

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.