By Alex Pashley

LIMA

As she wrings out children’s clothing in the rare winter sun, Hayde Zela is doing painstaking work in scarce water.

“One bucket is for draining, another for rinsing,” says the mother of five, pointing at seven tubs in the arid shantytown of Vizcachera. “Another is for separating the clothing, then we use what’s left for the toilet, before it all flows down the street.”

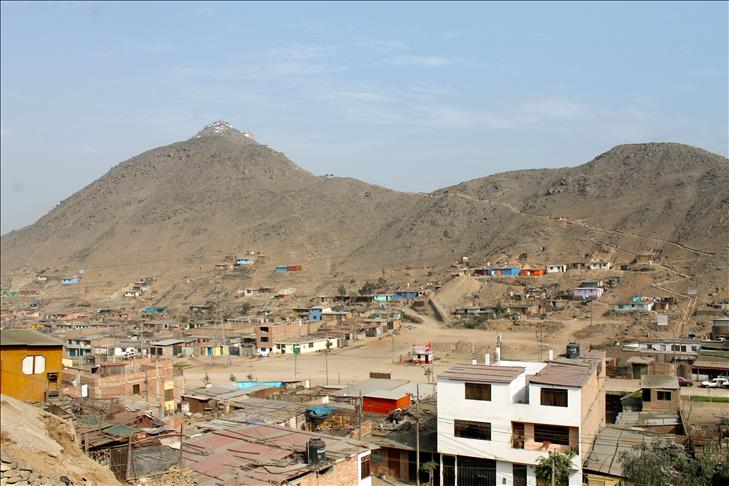

Located on the fringes of the world’s second driest capital after Cairo, Zela has reason to be thrifty: Vizcachera has made do without running water since its first migrants staked out pigsties in the 1980s.

Years of petitioning the authorities continue to go in vain for the town of 3,000, where persistent leaden skies drop just nine milimeters (0.35 inches) of rain a year.

Lima’s state-owned water authority, SEDAPAL, built two now-obsolete tanks in the barren hillside six years ago, and budgets and blueprints for a pipeline were outlined.

But protracted disputes over some settlers’ lack of land titles, and blurred jurisdictions regarding who’s in charge, leave many wondering if water will ever arrive.

“There’s a lot of poverty here,” community president, Serapio Meza, who first requested water in his first term in 1992, told the Anadolu Agency (AA).

“Today we’re almost the same. We have hardly advanced. We need help so this town can rise up.

Vizcachera’s ostracized poor lost faith in the state years ago, and along with 800,000 others in the 9 million population city, source water from unregulated trucks to fill cisterns and ramshackle barrels.

It’s untreated and comes at a premium – up to 20 times what connected households pay, according to the Peruvian Institute of Economics. Tuberculosis and stomach problems are chronic.

- Playing catch up

Vizcachera is like numerous ‘young towns’ that sprung up as a gradual rural exodus drained Peru’s provinces. The process intensified during the country’s civil war in the 1980s and 1990s – at its most bloody in the Andean highlands, and from where hail many of the town’s older generation.

With settlements clustered in the city’s extremes, the water authority is clearing a backlog of claims for basic sanitation.

It aims to extend the 93 percent now covered to 100 percent by 2017.

But a lack of land rights in towns that now resemble mini-cities put many in a bind, obstructing water’s arrival.

“There’s a high probability [full coverage] will happen,” Hildegardi Venero, an economist at the Institute of Peruvian Studies told AA. "A few months ago a master plan for Lima was published and a lot of money was concentrated in this objective,” though that doesn’t assure constantly accessible, clean treated water, Venero adds.

Though the water body’s $3.3 billion investment plan with the Ministry of Housing isn’t assured to hit the target, said company engineer, Javier Pajares Ribera.

“The idea of 100 percent coverage is a very nice one, but technically impossible. There are always new invasions, new demands, and when projects reach execution stage, new settlements appear.”

- Legal dispute

Vizcachera isn’t exempt. A continuing court battle over 42 hectares (104 acres) seized by settlers has dragged on for 12 years, while newcomers, magnetized by Lima’s economic opportunities, continue to arrive resulting in new invasions.

The town’s plight is complicated by its location. Officially named “Annex Two,” it joins several other waterless settlements a few miles beyond city limits, and out of SEDAPAL’s domain.

But a government directive brought it and other annexes under the water authority’s control to provide basic services, though the state of proceedings is unclear.

The village’s president said a committee will meet with engineers in November about the 150,000-sol ($54,000) water pipeline. The authority says more tests are needed in the unforgiving desert conditions, and has suggested villagers consider financing it themselves.

That stands at around 2,000 soles ($700) a household – nearly three months salary for those on Peru’s minimum wage for public workers.

- Residents are weary

“I feel we’ve abandoned hope because mayors and politicians on the campaign trail come and promise to help us, but never deliver,” says Herbert Raenz, a 23-year-old paper merchant.

“As they’ve said it to us various times, we’re untrusting,” said Rosa Cosinga.

- Future tests

Lima, a desert city, isn’t blessed with big water resources.

Its daily consumption – twice Paris’ per capita demand at 250 liters (66 gallons) and set to double by 2040 – is excessive and augurs future shortages.

To reverse waning basins as snowcaps recede because of global warming, authorities are building a grandscale reservoir 12,000 feet up in the Andes. It’s to boost the flow of the River Rimac, which supplies the city with 80 percent of its drinking water.

Though creaking infrastructure and a growing population continues to pose complex challenges.

Voters elected President Ollanta Humala on a leftist mandate to help Peru’s most needy through social programs.

The government’s water investment plan for 2014-2021 says “all countries in the short term must guarantee that all inhabitants in their jurisdiction enjoy access to these services at a quality and sufficient quantity to guarantee their well-being,” to comply with UN observations of human rights.

But at the capital’s edges, this is far from being achieved.

“In 30 years the water problem hasn’t been addressed and it’s a fundamental factor in our lives,” continues Raenz.

“Without it we have practically nothing.”

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.