By Nilanjan Dutta

KOLKATA, India

The menu lay on rows of tables, impressive: sweet bread, sherbet, fruit custard, halim (a mixture of stewed meat and lentils), and mutton korma – derived from Urdu and meaning ‘braise.’ Around 10,000 guests were breaking bread with Eastern Indian state West Bengal's Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee and other senior officials. During the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, during which believers fast from dawn to dusk, politicians of various hues celebrate iftar, the fast-breaking meal at the end of the day, by throwing parties to ritually connect with members of the "minority community" of Muslims. The eastern city of Kolkata holds what is dubbed as the biggest "iftar party" in the country.

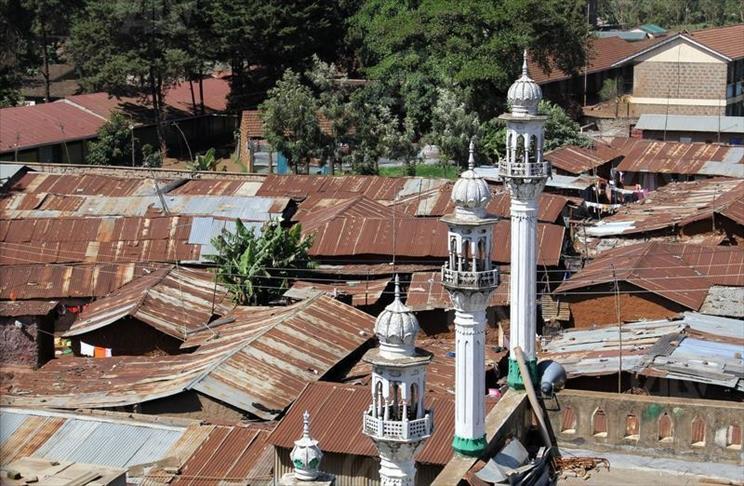

Not far from this grand feast, on this mid-July evening, a stark contrast: a white-haired, white-bearded septuagenarian gentleman calmly enjoys his cup of tea and a couple of biscuits. Sanjay Mitra, 71, had also observed the day-long Ramadan fast and he broke it the same way he does throughout the month: on his humble rooftop room, which is covered with corrugated tin sheets, sometimes joined by a friend or two. Once in a while, albeit rarely, he goes out to share a bowl of halim with his neighbors.

“Rajabazar (where he lives) is one of the few areas in the city where you get beef halim nowadays. Most of the famous eateries have put up a ‘No Beef’ sign to prove that they are willing to adopt the culinary culture of the majority,” he observes, referring to the Hindus who constitute more than 80% of India's population. Most consider cows to be sacred and do not eat beef.

By the way, Sanjay Mitra is a Hindu.

Why does he observe roza (fasting) during the month of Ramadan every year even though he is not a Muslim? A few months after the Babri mosque in the northern Indian town of Ayodhya was demolished by Hindu militants on December 6, 1992, Mitra was in Delhi, confounded.

“I felt ashamed as a Hindu,” he recalls. “It seemed pathetic to me that the majority community was not stirred by the horrible act [committed] by a few of its members. I was searching for some ways to register my protest, express my solidarity with the community that was under attack and at the same time, purge myself of the intense shame. The following year, I began fasting during in Ramadan.” Which he celebrates in his own way.

Namaz (prayer) five times a day, he decided, was not for him. Instead, he only joins the Eid Namaz - the prayer marking the first day of festivities following Ramadan - which gives him a feeling of “being with everybody on a festive occasion”. He cares little for political correctness; he cares less for religious correctness or whether members from either community object.

“Most of the people who know me have taken it in good spirits, especially here in Rajabazar where I have spent my childhood. All my Muslim friends in fact encourage me,” he says, without missing the punch-line: “As for the rest, I don’t care.”

But, if he really wanted to bridge the two communities, his wife Sumitra asked him one day ten years ago, why did he not observe a Hindu fasting as well. Mitra readily agreed, but for one stipulation. “I will not observe any higher-caste ritual.” India's thousand-year-old caste system still defines the status of hundreds of millions of people in the country. He began fasting during the month of Chaitra (mid-March to mid-April), which leads to the “lower-caste” Gajan festival, associated with the deity Shiva, among others. To unite two communities, Sanjay Mitra fasts for two months during the year.

He asserts that fasting has an uplifting effect on his body and mind. At 71, he feels a little stressed towards the end though, “during the last 10 days or so”. However, he vows to carry on as long as he lives.

Mitra has always been an “activist,” fighting for various causes. He was one of the founding members of the Association for Protection of Democratic Rights (APDR) and even spent two years in jail between 1975 and 1977, when the human rights organization was banned. Previously, he had been involved with the far-left Maoist Naxalite movement, which staged an uprising in 1967 in West Bengal, later severely repressed by the Indian forces. But Sanjay does not wish to dwell on his political involvement.

Since then, he has fought for causes as a professional photographer for Amnesty International, among others. In 2012, he anchored a documentary, “Sanjay and Sumitra: the Tiger and the Typhoon”, on the Sunderbans, the largest mangrove forest in the world and home of the Bengal tiger.

Italian filmmaker Tommaso D’Elia introduces him thus: “Sanjay Mitra, born in Calcutta in 1943 survived the great famine that killed about 1 million Indians. A born survivor, (…) he defines himself as a social activist.”

A social activist who has a habit of taking up the custom of a battered community as a symbol of solidarity and protest. During the anti-Sikh pogrom following Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, he was in New Delhi too. Since then, he sports long hair and beard, much like… a Sikh!

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.