ANALYSIS - An era of renewed 'smart' diplomacy between Iran and the US

Nuclear diplomacy surrounded by uncertainty as dynamics of the negotiation climate evolve

The author is an instructor at Sabanci University, with her research focusing on Iranian foreign policy, security and military culture, Shia geopolitics, and the Axis of Resistance in the Middle East

ISTANBUL

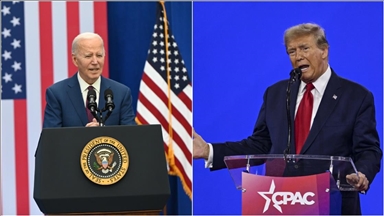

A process of renewed nuclear diplomacy has kicked off between Iran and Joe Biden, who took over the US presidency on Jan. 20. The mood of optimism, prompted by Biden’s signaling that he would return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) once elected, has been replaced by uncertainty as a result of the precondition he put forward for a return to the deal, which stipulated that Iran, in compliance with the relevant JCPOA provisions, should immediately cease the nuclear activities it resumed. While the issue of “who will be the first to fulfill their obligations under the JCPOA” dominates discussions between the two parties, Iran’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Javad Zarif called for a “coordinated and synchronized return” to the deal under the mediation of the European Union (EU). [1] On the other hand, Biden’s rejection of this call for a synchronized return to the deal led to the questioning of Biden’s seriousness and willingness to resolve the Iranian nuclear issue.

The answer to “Could JCPOA be revived and sanctions on Iran lifted during Biden’s term?” must be sought in the “dynamics of the negotiation climate” and the “balance of bargaining power” in the negotiations between the two sides, not in Biden’s attitude. The truth is that the JCPOA whose negotiations began in 2013 and the JCPOA which is expected to be re-implemented in 2021 are fundamentally different agreements. The actors involved in the negotiations, the basic bargaining issue on which these actors agreed, and the post-bargaining experiences regarding the agreement process have brought the agreement to a whole new level. Therefore, to accurately interpret the ambivalent attitude of the Biden administration towards the agreement, as well as the future of the agreement, it is a must to take a look at the bargaining dynamics in question.

Three phases of JCPOA

The success of international agreements depends on the dynamics intrinsic to the negotiation climate out of which they are borne. As the actors involved in these negotiations, the main bargaining issues that the actors agree upon, and the experiences related to the post-bargain settlement processes change, expectations regarding the success of the agreements in question will also change.

In this regard, JCPOA can be described as an extremely complicated international agreement due to the drastic changes observed in its negotiation climate between 2013 and 2021. The agreement has passed through three distinctly different phases in the last eight years: the visionary diplomacy period of 2013-2017, the maximum regression period between 2018-2020, and the revived ‘smart diplomacy’ period since 2021.

2013-2017: Visionary diplomacy period

JCPOA is the product of a very unique yet short-lived window of opportunity created by the US and Iran to move bilateral relations onto a positive ground by trying to turn the nuclear crisis into an opportunity. With a history of bilateral relations fraught with radical ups and downs, both sides took advantage of their favorable domestic political climate at the time. The vision of the agreement is based on the Obama administration’s ideal to gradually transform Iran from within, with whom the US could not come to a mutual understanding regarding their common interests at the international and regional levels due to the latter’s “international revisionist state model” adopted following the 1979 revolution, and to make Iran a legitimate and effective part of the international system working in harmony with fundamental US interests by the use of certain economic and political incentives.

On the Iranian side, the counterpart of this vision was Hasan Rouhani’s moderate government, which was relatively compliant with the norms and components of the international system, open in principle to the idea of international negotiation, and came to power as a representative of Iran’s urban middle-class culture and as a promising actor for the future of the pragmatist-reformist political alliance in Iranian politics. A featured aspect of this period was that Iran’s foreign policy was conducted by two actors based on two different visions, with the Middle Eastern dossier being managed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), which was now increasing its military mobility in the region, while its nuclear dossier was handled by the pragmatists. American democrats, along with all of their politicians, bureaucrats, and regional experts, collectively turned a blind eye to this obvious division; Iran’s military activities in Yemen and Syria were deliberately kept out of the world agenda, and nuclear talks were framed with the strong rhetoric of a “historic deal” in bilateral relations.

2018-2020: Period of maximum regression

The Trump administration adopted a policy of maximum pressure, which was the complete opposite of Obama’s strategy to coopt Iran to monitor its revisionist foreign policy. This policy maximally transformed, for the worse, the chief items subject to negotiation that the Obama and Rouhani administrations had agreed on, as well as Iran itself and the negotiation atmosphere in both countries. Trump primarily argued that the two-dossier, thus conflicting, foreign policy of Iran should be handled as a single dossier with a holistic approach. In fact, shortly after taking office, he terminated the JCPOA, which focused exclusively on nuclear armament, not because Iran had failed to comply with its nuclear commitments, but due to concerns about the IRGC’s increased efforts to support Shia militias in the Middle East. This situation suggested that Iran’s nuclear armament problem should be renegotiated in conjunction with the IRGC’s Middle East strategy in the future – an already grand issue in and of itself. Also, Trump expected Iran to undergo a transformation from within because of the heavy economic sanctions. And this meant a total regime change by the Iranian people, who were buckling under economic depression and thus were expected to overthrow the whole administration from within, along with all its military conservatives and pragmatist-reformers.

Trump, however, failed to recognize one fundamental requirement for any regime change. Political regimes change not when people want it, but when they get the support of the military against the regime. It just did not seem likely for such an ideological army that was constitutionally charged with ensuring the survival of the Islamic Republic against all internal and external threats and benefited from all the economic and political advantages supplied by this obligation to turn its back on the current regime in the short term. Indeed, the policy of maximum pressure not only failed to overthrow the regime but also strengthened the conservative military wing and ignited a whole new debate around [the complete] ineffectiveness [of the negotiations] among the Iranian people, which could result in a categorical rejection of pragmatist-reformist politics. Lastly, Trump’s termination of the agreement and imposition of heavy economic sanctions on Iran, as well as the assassination of Qasem Soleimani which shocked the world, served to amplify Iran’s distrust of the USA and JCPOA. These major crises experienced during the implementation phase of the agreement shook the foundation of trust to its core -- a foundation indispensable for the survival of the bilateral negotiations between the two sides.

Post-2021: Renewed 'smart diplomacy' period

Regarding the JCPOA issue, the Biden administration inherited wreckage much worse than assumed when they took office. First of all, the issue that Biden has taken on is no longer just the main issue agreed upon in the JCPOA, which was nuclear activities. He has rather inherited a whole set of issues with all kinds of implications and potential repercussions, ranging from Iran’s nuclear program to its ballistic missile program, and from its efforts to recruit Shia militias in the Middle East to its relations with the countries in the region. Moreover, it appears that the Iranian counterpart of Biden whom he will face at the negotiating table over this complex package of issues will change as well. In the Iranian presidential elections scheduled for June 2021, it is highly likely that a president of military origin, representing the conservative military wing in Iran, will take office. Finally, the fissured ground of trust over the agreement poses a major challenge for any diplomatic initiative that Biden could take. However, Biden was well aware of the very wreckage he was taking over despite his optimistic campaign promises. In fact, in an opinion article that he wrote in September, he said that “...there is a smart way to be tough on Iran”. [2] As stated, Biden will implement a strategy of “smart power”, in which he would combine moderate and coercive strategies in line with the requirements of the current realities while remaining open to diplomatic negotiations in principle. This strategy is based on a delicate reconsideration of the balance of bargaining power between the two countries in the light of this new negotiation climate.

Iran’s bargaining power against Biden

Contrary to popular opinion, we see that the bargaining power balance between the USA and Iran is in favor of the latter due to the dynamics of the negotiation climate inherited by the Biden administration. In this context, we can list three trump cards held by Iran:

First of all, a distinctive feature of international bargaining processes is that actors whose hands are tied in domestic politics tend to have greater leverage on bargaining processes at the international level. Today, we see a moderate Rouhani government besieged on all sides by Iranian state power, with political power controlled by military and religious conservatives through various institutions.

Iranian conservatives who want to weigh in on a possible nuclear diplomacy process between US democrats and Iranian moderates passed a bill in December entitled “Strategic Action Plan for Lifting the Sanctions and Protecting the Interests of the Iranian Nation” in the Iranian parliament, where they constitute the majority. Endorsed by the Guardian Council, the bill prescribed raising the uranium enrichment levels to at least 20%, which was previously set at 3.67% by the JCPOA, and also increasing the number of enriched uranium stocks. [3] The same bill asserted that Iran would withdraw from the Additional Protocol to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapon and limit all international inspections over nuclear facilities unless the US sanctions that hit Iran’s banking and oil sectors were lifted by February. [Ibid.] Zarif is implying that his hands are tied against the Biden administration’s demands for the cessation of nuclear activities due to the bill passed by the Iranian parliament and the prospect of the military conservatives coming to power within a few months, but on the other hand that Biden may make a proactive move as head of state, issue an executive order in favor of lifting the sanctions, and thus revive the nuclear deal, as he is not confronted by such obstacles in domestic politics. What we are seeing is a pragmatist Iranian government reinforcing its international bargaining power by acting in full coordination with the constraints imposed by the military conservatives at home, while suggesting to the Biden administration that the window of opportunity for reconciliation is narrow. “You have to reach an agreement with us in synchronized steps at least, otherwise you may miss this opportunity,” the Iranian side is implying. Using this trump card, Iran is not backing down in the game over “who will be the first to return to its JCPOA obligations”, thus leaving the responsibility to the other side.

The second major trump card Iran uses is the nuclear activities that it has accelerated. The raising of the uranium enrichment to the pre-agreement levels of around 20% means that the time Iran needs to achieve a nuclear weapon production capacity has significantly decreased. In fact, there is heightened concern among the US and other countries in the region that Iran would be able to achieve this capacity within six months. [5] This turns out to be a serious trump card for Iran that will push the Biden administration to move rapidly towards reconciliation.

The third trump card of Iran is the excessive use of economic sanctions during Trump’s term. Iran is perceived as a victim in the international community due to the humanitarian costs that had to be borne as a result of the sanctions, while the US is in a questionable position as it withdrew from the agreement and imposed harsh sanctions on Iran. Iran is taking advantage of the US-created humanitarian problems in front of the international community, especially those created during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, the case brought by Iran to the International Court of Justice in 2018 concerning the humanitarian costs of the sanctions was accepted. The court stated that the US sanctions imposed indirect restrictions on Iran’s medical, pharmaceutical, civil aviation, food, and agricultural product industries and that it could hold a hearing for lifting the sanctions. [6] This means that the legitimacy of the heavy economic sanctions levied by the US has begun to be questioned internationally.

The Biden administration holds only one trump card against the above-mentioned three cards held by Iran: Economic sanctions. Biden rejected the EU-mediated synchronized action plan proposed by Zarif not because the Biden administration is not any different from the Trump administration as claimed, but because he is aware of his relatively low bargaining power at the moment and does not want to spend his only trump card of sanctions yet. Biden demonstrates willingness and seriousness to address the nuclear issue with Iran. We can acknowledge this by looking at his critical appointments to the Iran dossier, including figures such as Antony Blinken, Jake Sullivan, and Robert Malley, who played active roles in the nuclear negotiation processes during the Obama term. On the other hand, this eager administration is no stranger to the reality of the present bargaining climate, which has undergone dramatic changes in the last eight years, either. Biden is building a smart diplomacy strategy that we could still describe as solution-oriented, realistic, and cautious, albeit relatively weak in the face of Iran. Accordingly, what possible scenarios might prevail in the smart diplomacy strategy of the Biden administration is a question to be further tackled.

Possible scenarios regarding the future of JCPOA

During Biden’s term, the following interrelated scenarios regarding the future of JCPOA stand out:

The Biden administration envisions a two-stage process regarding JCPOA. Biden’s priority for the first phase is to immediately put a stop to Iran’s acceleration of nuclear activities and to extend the time required for it to achieve the capacity to produce a nuclear weapon as much as possible. While Biden does not prefer to take the first step for lifting the sanctions, he is trying to convince Iran’s moderate government through the above-listed names assigned to critical positions to take the first step and to return to the agreement before the elections in June. In this context, Biden may have to ease some of the sanctions, but it does not seem likely that he would lift the sanctions all at once, for he has to use his only trump card extremely judiciously and bit by bit.

On the other hand, the second phase of the agreement expected to start in June provides more details as to why the sanctions could not be lifted all at once in the first phase. The Biden administration plans to prepare a comprehensive follow-up agreement. The follow-up agreement envisages the negotiation of the collective package of issues (including the Ballistic Missile Program, Iran’s Shia militia recruitment activities in the Middle East, and relations with other countries in the region, all irreversibly brought to the world agenda by the Trump administration, in addition to the nuclear program) on an international platform that will bring together the US, EU, Iran, and several other countries in the region. The Biden administration is waiting for the elections in June for the follow-up agreement. In fact, its new negotiating partner for a comprehensive follow-up agreement will be the new government of Iran that will take office after the June elections. It appears that this follow-up agreement will turn out to be a much more complicated and longer process due to the existence of multiple main issues in the agreement, the increased number of actors to be involved in the negotiations, and the current uncertainty surrounding Iran’s domestic politics. It seems that the Biden administration will manage the bargaining process with the promise of gradually lifting the sanctions in this long-running, multi-actor, and multi-themed negotiation process.

Based on these indicators, it could be anticipated that the renewed smart diplomacy period that began with Biden will proceed with moves that are eager and solution-oriented, but also cautious and challenging, due to the transformed dynamics of the negotiating climate and the bargaining power of both sides.

*Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Anadolu Agency.

Translated from Turkish by Can Atalay

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.