Bangladesh's tech start-ups eyeing development

A new group of technology start-ups in Bangladesh's capital Dhaka are focusing on innovations that will help the country's development

By Kaamil Ahmed

DHAKA, Bangladesh

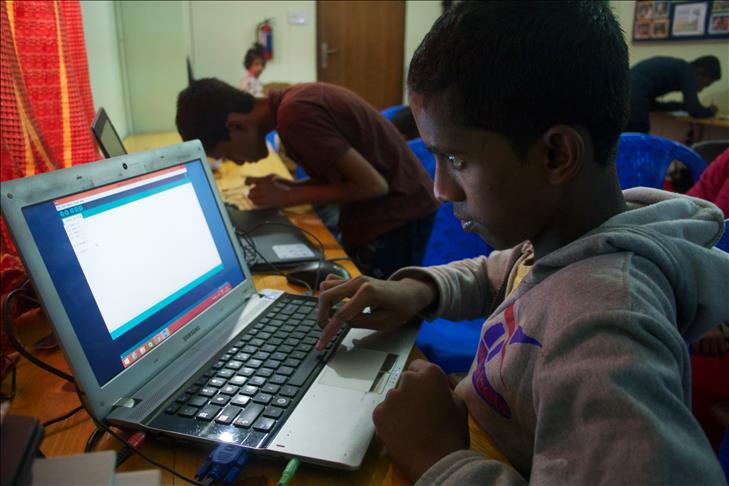

Every Friday, 14-year old Pakhi spends her morning in a room in Dhaka’s low-income area of Notun Bazar, learning how to build and operate robots.

The class is still in its early stages -- she’s learning how to control LED lights with short pieces of computer code -- but Pakhi is ambitious about how she could use the skills she is learning.

“I want to make things you can control, like lights and fans, with eye contact and hand movement,” she says.

“I want to make a living out of this. In case I have to leave regular school at least this gives me something I can do and have opportunities,” says Pakhi. “I want to be a doctor, but if I can’t, I can be an engineer.”

The space and equipment are provided by a group called CAFFE, Computers are Free for Everyone, and the teaching by Shams Jaber, 24, and Neloy Anik, 22, who founded The Tech School.

They are part of a nascent start-up scene sprouting in Bangladesh’s capital, which is focused on using technology to push forward the country’s development and balance out its inequality by helping the underprivileged.

Jaber and Anik founded The Tech School after dropping out of university, tired of the lecture-based, theory-heavy system which they felt was not giving them enough useful practical experience.

"We had the broad dream to reinvent the education system,” says Anik.

After initially trying to teach a six-subject curriculum, they settled on robotics, a subject that gives the children practical tools for innovation. “We give them the basic skills, and let them to do the rest,” says Anik.

Anik and Jaber use the income from a class for middle-class children in Dhaka to support other projects, including the Notun Bazar class and another in Bandarbans, a remote tribal area near Bangladesh’s border with Myanmar. They are also planning to start more projects in other rural areas.

“One of the projects will be to create micro hydroelectric energy, it’s a little tube that can provide local power,” says Jaber, who spends a week with the children in Bandarbans every month. “It will mean they don’t have to walk two kilometers to recharge their laptops, which is what they’re doing now.”

“These are the real life projects that we think can help society,” says Jaber.

He and Anik point out that by working with robots, instead of only focusing on computers, the children are learning how to gain engineering skills for both hardware and software.

“For Bangladesh, the hardware revolution hasn’t really begun. They think about software and websites. What we haven’t made happen here is hardware that solves problems,” says Jaber. “Power is a big problem here, which is related to hardware. Hardware is the place where we can excel.”

The focus on software Jaber mentions is linked to the country’s fast-growing IT sector, which has mainly focused on providing outsourced labor for international companies who want mobile apps, software or simple tasks like data entry done cheaply.

Many in the loose collection of young entrepreneurs, university dropouts and socially-driven activists that forms Dhaka’s new start-up ecosystem have more ambitious ideas about how to use technology.

“We want innovators that have a social impact,” says Saif Kamal, founder of Toru, an incubator for social enterprises. “But we don’t have the actual institutions to support this. There’s a gap there.”

Filling that void to create businesses that address Bangladesh’s problems with clean water, sanitation and sustainable agriculture is, Kamal says, the responsibility of local groups, not foreign aid or investors.

“You can’t sit in another country and solve Bangladesh’s problems. Just like you can’t create an app serving America in Bangladesh,” he says. “The issue is understanding what is going to work in a Bangladeshi context, rather than plugging and playing a global solution.”

Kamal’s goals bear a resemblance with the Bangladesh government’s vision for a “Digital Bangladesh” which would use technology to tackle issues in areas like education, health and poverty reduction. However, most in the country’s start-up scene are working independently, wary of the complications and conditions that are usually married with official funding and foreign aid.

According to Kamal, start-ups in Bangladesh often rely on winning grants to build prototypes of their innovations but rarely find any further support.

“Innovators are a different breed altogether and most of them don’t have global exposure,” says Kamal, who says the idea behind Toru is to give socially-driven entrepreneurs the business skills to make their projects sustainable. “We are just exploring the landscape of start-ups. There is a lack of understanding of consumer behavior; what is going to work and what isn’t.”

CodersTrust, a group founded in Denmark but operating in Bangladesh, has focused mostly on training people for employment, and has a particular interest in helping women. They provide micro-finance loans that allow students to support themselves while taking the CodersTrust training.

“Then they come on our platform, learn how to code. Then with that knowledge, we link them up with the jobs on the freelancing market. That’s the beauty of it,” says co-founder Jan-Cayo Fiebig. “You only need a laptop and an internet stick and then you can bid for and do the work for a job in Silicon Valley. The company doesn’t give a rat’s ass where this person is [based] as long as they have the skills.”

“There’s no coding background required. Because the idea is we don’t want to be for the best, the top notch, we want to be for the masses, we want to give everyone an opportunity. Otherwise that wouldn’t fit with our vision,” he says.

Fiebig hopes that by training women, they can provide them with flexible skills that allow them to competitively enter Bangladesh’s freelance market which, with 500,000 freelancers, is the third largest in the world.

“What we’re seeing with our current students is the best students are women,” says Fiebig. “We see the women have this approach of learning and are persistent. They just want to know it.”

He points out that while many of the female students may not be able to take full-time employment because of family responsibilities, freelancing gives them freedom to work.

“Why not give this woman a laptop and a dongle so when the kids are sleeping she can work from home and empower [herself] and provide something for the family?” says Fiebig. “I think this is just such an easy way to go about it.”

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.